The End of History Illusion

Embracing Change and Ambiguity

At each stage of life, we’re faced with decisions that define our future. As we grapple with these decisions, we overemphasize our current preferences and underestimate the changes that we’ll experience in the future. Your favorite band today, will likely not be as important to you in ten years. This phenomenon is called the “End of History Illusion.” It states that, despite knowing that our preferences have already changed, we predict that our preferences will largely stay the same in the future.

History is littered with failed predictions. Complex environments with changing circumstances make it difficult to accurately predict future states. While the world outside is changing, we’re each changing inside — and we’re utterly incapable of predicting these changes within ourselves.

Don’t believe me? Try this little experiment.

Flawed Forecasters: Reflecting and Predicting Our Preferences

Most people believe they know themselves well enough to predict who they’ll be in the future. Before I expose the data backing this research, let’s do a little test to see how accurate we are.

To begin, take a minute or two to write a few simple sentences that describe a few details about your life. These sentences could include attributes of your job, your family, your favorite hobbies, or anything of interest. For example:

I’m an entrepreneur and product designer. I’m currently living in Seattle and designing a house in Chelan with my partner, Kelsey. We have a 2-year-old Bernese Mountain Dog and spend our days working from our apartment in downtown Seattle.

Now, reflect back to where you were ten years ago. Would you have predicted your life would turn out this way? I know it’s difficult to assess, so just do your best and try to be honest with yourself.

If you feel like you would have predicted the life and interests you currently have, congratulations, you are among the few. Want to test your skills for future-you predictions? Continue with the next exercise.

Look ahead 10 years and write a few more sentences about your future that are specific enough to prove or disprove using the following format:

I will work in [industry/job].

I will live in my [house or apartment] in [location] with [partner + kids + pets].

My favorite bands will be [top three bands].

My favorite vacation location will be [location].

[Insert your own prompts as-needed].

Write these items in a calendar event for ten years in the future. Be sure to set a reminder to review your answers and reflect on their accuracy.

This was the exact experiment that Daniel Gilbert and his colleagues ran with over 7000 participants in 2013. The research was named after Francis Fukuyama’s prediction that liberal democracy was the final form of government, or as he called it “the end of history.”

Half of the participants were asked to report their traits, values, and preferences along with what those metrics had been ten years earlier. The other half of the participants were asked to describe those metrics in their present selves and to predict how they might change in the next decade.

Researchers reported the degree of change that each participant reported or predicted. The results were overwhelmingly conclusive: participant’s predicted the bulk of their changes were already behind them.

Furthermore, this illusion was consistent across age groups. For example, a 20-year-old expected to like the same music when they were 30, but 30-year-olds no longer had the same taste as when they were 20. While older people changed less than younger people, they underestimated their capacity for change just as much.

We might believe we’re great at envisioning our future, but maybe our dreams are simply a reflection of our past. If we can’t see the future, should we even try?

Short-Term Diversification

“In most of our decisions, we are not betting against another person. Rather, we are betting against all the future versions of ourselves that we are not choosing.”

We tend to make plans based on the data that is currently available to us. If we like modern homes today, we assume that we’ll also like them in 30 years. The conventional approach is to solve our prediction problems with more data. Unfortunately, when it comes to our preferences, we’re lacking in additional data needed to predict changes.

We tend to look for patterns we recognize, which is, in part why we often fail to predict our futures. We’re only using historic data to inform our views of the future.

We’re bad at translating current preferences into future predictions. What’s not clear is how we should deal with this issue.

What if we instead ditched our long-term plans altogether?

Before you run off, let me explain! Ditching long-term plans does not mean giving up on planning. Instead, I’d suggest another approach to the traditional method of planning. A more flexible model that embraces, and is also designed for constant change.

Enter: diversification.

Diversification is a common investment strategy that is designed to reduce risk and create optionality. Instead of solely investing in a single decision with consequences associated with a future you, diversification allows for flexible goals.

For example, if you want to write more, instead of requiring a minimum word count each day at a specific time, you could change the plan to be just write something every day. Creating flexibility allows for a more fluid exploration of values and preferences without detracting from goal-seeking behaviors.

Diversification maintains optionality, which creates opportunity.

Many people build their entire life around a few key decisions. Who will I marry? Where will I live? What job will I take? This strategy delivered positive results when the rate of change was low. As technology accelerates, so do the complexities and rate of change.

Embrace Change

Whether you’re 26 or 62, the “End of History Illusion” blurs your predictive abilities all the same. As humans, we’re susceptible to the idea that we exist as finished products. This can lead us to overinvest in future choices based on present preferences. In reality, we’re a work-in-progress. Our greatest mistake is to assume we’re done evolving.

Changes in the work environment are a great example of our poor preference predictions. If you had asked me ten years ago if I’d be able to work from my home every day, I would have likely predicted that it would be technically possible but that I’d prefer to be in an office. That prediction would have, at the very least been partially inaccurate.

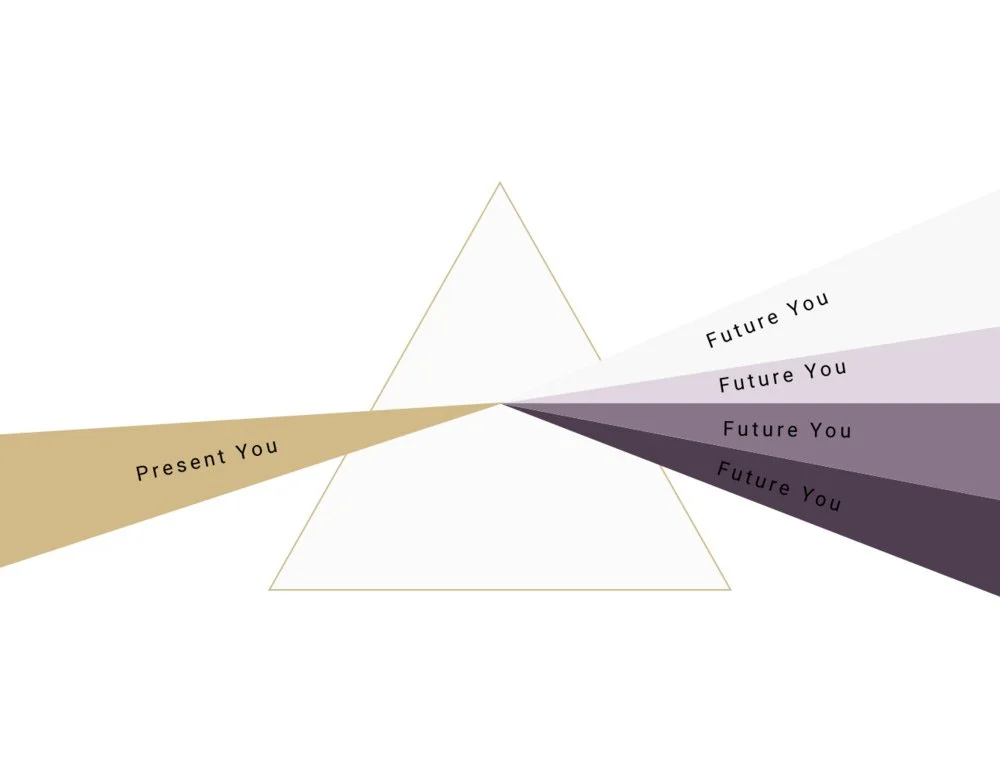

Our predictions experience a refraction, like a prism. As we experience events, we reshape our future, creating new paths and opportunities.

As we continue to experience dramatic changes in our environment, we need more optionality and diversification. For every single bet you place, consider placing another bet that creates future optionality. There are no systems (yet) that predict what our preferences will be in the future — so we must diversify, adapt, and change.

If one thing is true, it’s that the only constant is change.

Embrace it.