Path Nine

As newsletter to help high-achievers chart new paths to earn more, work less, and live better.

New here? Take a look at one of my popular essays and subscribe to support my writing!

Continue reading… ↓

Inside the mind of a tinkerer

A more playful approach to work and productivity.

After lunch on a Sunday afternoon as a kid, I’d often hear my dad proclaim that he was going to ‘tinker’ in the shop. Despite the regularity of these Sunday tinkering ventures, I had no idea what he was it actually entailed. I was more focused on getting out of chores or yard work.

Now that I’m much old(er), I better understand what he meant by tinkering.

Tinkering is work, but it’s also not work.

It’s the kind of work that doesn’t require deep thinking or focus.

For me, it’s the stuff I can do slouched down on the couch with my laptop and The Office playing for the 348th time in the background.

For him, it was rearranging tools and cleaning up his workspace.

In many ways, it isn’t really work at all.

It’s neither hard nor laborious.

It’s both tedious and stimulating.

It’s unfocused and yet engaging.

It’s just…tinkering.

Tinkering—often mistaken for aimless activity—is a crucial foundation for creativity and innovation, providing the mental space necessary for ideas to gestate and evolve.

The act of tinkering is akin to wandering through a garden instead of marching down a path. It's not about deep focus or intentional outcomes. It's all tidying up vs. deep cleaning.

Tinkering is like a music playlist, blending work and life seamlessly. It's not always about striving for capital-P productivity but about activating new ideas through relaxed exploration. By giving ourselves the freedom to tinker, we create space for true creativity to flourish.

In exploring the essence of tinkering, I see found parallels in writing this piece. Like a tinkerer joyfully engages in tasks, such as rearranging pixels or sending emails, I've been tinkering with its ideas, words, and paragraphs, allowing my thoughts to evolve and take shape over time. Instead of leaving you with the final draft, I’ve opted to include them because, as any writer knows: showing always beats telling.

Though I’m sure it makes this article harder to read—maybe that’s the point. By engaging with the variations iterations of an idea and ignoring the modern tendency to only show our best work, we lose the opportunity to truly be creative. The process of experimentation, refinement, and playful productivity is what tinkering is all about.

"Creativity is allowing yourself to make mistakes. Art is knowing which ones to keep." - Scott Adams

It’s a bit unhinged, but in a world where we’re always showing the Instagram version of ourselves, we need more space to let the bad ideas fly, show behind-the-scenes shots, and iterate. Good ideas come through iteration and self-exploration, not striving for perfection.

The funny thing is that a lot of our modern work culture is digital tinkering.

So what is tinkering?

Tinkering with ideas is a playful exploration or a taking of inventory. It's about noodling and letting bad ideas fly pass by so you can discover the good ones. This light, unfocused work prepares for deeper, more meaningful creative work. Letting 1,000 flowers bloom requires some weeds to take root, the key is not to pluck a flower-looking weed or weed-looking flower too early. Creativity requires time to grow and develop.

Tinker-Core: Balancing Shallow and Deep Work

In productivity and creativity, tinkering is the connective tissue between the realm of shallow work and the domain of deep work. Tasks like organizing emails or reading documents can be the first step towards deeper work, a warming of up the creative engines so to speak. By allowing ourselves to tinker with ideas and concepts on a surface level, we create a foundation for deeper exploration. Tinkering, with its playful and exploratory nature, acts as a precursor to the focused attention and immersion required for deep work, enabling us to transition from light experimentation to substantial creativity.

Tinkering takes various forms but has consistent characteristics:

Multi-taskable - the work can be done with sports or a podcast on in the background.

Highly-variable - the task might not be clear until you’re in it the journey is the destination.

Optional - the work isn't critical, but it's necessary for productivity.

Tinkering is the shallow work we do to keep the hedonic productivity wheel turning. We know we’re supposed to work, so we do. In modern, Americanized work cultures, work is the only true form of fulfillment, value, and meaning—happiness is exists only for the productive. If productivity is next to godliness, the lack of productivity is the deepest a form of depravity.

Done right, tinkering is productive and therapeutic. Done wrong, tinkering is it’s nothing more than feckless wandering.

Tinkering, like a gardener pruning with care, can cultivate creativity and productivity. Yet, aimless tinkering is akin to a lost sailor adrift at sea, lacking direction and purpose.

Tinkering is the gentle stream that guides creativity toward its destination, channeling ideas into productive waters. But without a map or compass, tinkering may become a wandering cloud, drifting aimlessly in the sky.

In the words of J.R.R. Tolkien, 'Not all who wander are lost.' Just as wandering holds purpose, so does tinkering. Embracing a playful approach to productivity can lead to creative breakthroughs. Let's label our tinkering correctly and explore the value it brings to our work and lives.

Our work shapes how we think about it; it is a self-fulfilling prophecy. We often categorize tasks as 'work,' attaching a sense of importance or obligation to them. But what if we reframe these activities as tinkering as a way to decrease friction and find ways to reconnect with a more playful form of work? Emailing, reading documents, or sending Slack messages may not require deep thinking or effort, but labeling them as 'work' can make us feel productive. Are we becoming modern-day pencil pushers, engaging in activities that may not involve intense labor but still provide a sense of productivity?

The Value of Tinkering Across Contexts

For me and my dad, tinkering was a mix of playful productivity and therapy. It was a way to feel productive without the stress of actual work (aka the big, haunting tasks you’re avoiding). Tinkering offers a stress-free way to feel accomplished, and potentially enjoy yourself. And for people like me who struggle with perfectionism, anxiety, and intense ambition, finding ways to enjoy work while also feeling a sense of accomplishment is critical. When we push too hard, we end up going backward. It’s like having a fixed gear bike; you can pedal hard, but it’s better to go at the bike's pace, lest the chain comes off.

In the realm of everyday creativity tinkering lies a path to flourishing, as illuminated by a study titled "Everyday Creative Activity as a Path to Flourishing" by Tamlin S. Conner, Colin G. DeYoung, and Paul J. Silvia in The Journal of Positive Psychology. Their insightful research explored the daily lives of 658 young adults, revealing a fascinating cycle: engaging in creative endeavors led to elevated positive emotions and a heightened sense of flourishing the following day. This suggests that nurturing our creativity not only enhances our well-being but also fuels a continuous cycle of creative inspiration and fulfillment.

Whether you’re an entrepreneur or a corporate employee, modern work requires balance, but it can be hard to find. As I’ve written before, there are many ways of working. I'm most fulfilled when I alternate between work and life, combining elements like a guitarist or bassist.

While this approach works for me, others find it jarring or impractical. But it works for me because I spend time tinkering, sitting, thinking, keeping my mind and hands busy, not always worrying about a strong drive for capital P productivity, but activating nascent thoughts and ideas by taking my mind off them.

Organizing my to-do list is never my top priority. Just like organizing and labeling the tools in the shop were not my father’s priority. But this is the preparation for creative thinking and working—the clearing of mental clutter and RAM for productivity’s sake. Completing it in the quiet periods allows you to capitalize on your full creative potential when the opportunity arises.

If my work is a mess and I try to sit down to write, I feel the pull of the unmanaged work, nagging me to attend to it. But when I tinker unproductively, I create more space to think and create, even if not immediately. Gustave Flaubert reminds us that we should,

"Be regular and orderly in your life, so that you may be violent and original in your work.”

Reframing helps me avoid deciding when to work and reduces the anxiety of doing the work, allowing me to put real effort toward it when the time comes.

Maybe this won’t work for you, but it’s been helpful for me.

In a world where productivity is often measured by output and efficiency, the concept of jobs for individuals who simply enjoy tinkering 24/7 seems refreshing, albeit somewhat unrealistic in the near future. Imagine a workforce where individuals are encouraged to explore and experiment without the pressure of traditional work demands. Allowing time for more people to tinker could not only lead to innovative products and ideas, but also foster a unique sense of fulfillment for more of our workforce.

As I think about the impact what the future looks like for tinkerers like me, I imagine AI and Universal Basic Income will play an important role. But that’s an idea for another day, and another time.

Embracing our inner tinkerer allows us to revisit the joy found in unrestricted exploration, blending work and life into a harmonious rhythm that nurtures rather than drains. In this space, we don’t just work—we play, explore, and ultimately, flourish.

Requiem for an Office

What I miss about the office, and what I’m doing about it.

Acquisitions are weird.

One day, you’re doing your job and things are going well.

The next, you’re working for someone else and hearing that nothing will change.

It's akin to waking up from unconsciousness: the room spins, disorientation sets in, and you’re unsure where you are or how you got there.

In the blink of an eye, the familiar rhythms of my job were upended, ushering me into a new reality where, unbeknownst to me at the time, the seeds of my journey into the future of work were planted. That wild journey led me to a lot of interesting things; last minute international travel, 11pm conference calls, and my introduction to the always-on work culture I’d come to accept as normal.

But most interestingly, it led me to a core feature of what I’d come to see as a key component of the future of work: remote work.

I started working remotely in early 2013. It wasn’t really on purpose, nor was it in vogue. Prior to 2013, remote work wasn’t something people thought a lot about. Outside of support and call centers, or the occasional ‘telecommuter,’ it just wasn’t part of the work vernacular.

And it certainly didn’t feel natural in 2013.

If you look at this chart from We Work Remotely, you can see that the number of jobs listing for remote workers has grown by nearly 1200% in that time.

But honestly, it really didn’t feel like it.

There was no grand “welcome to the remote work party” banner. No strong cultural pulse that brought remote work to the forefront. If anything, remote work was considered a backup option, for specific circumstances like disabilities, outsourced roles, or consultants. It wasn’t mainstream or understood.

I stumbled into a world without borders by accident. At the time, I was working for Deloitte consulting. My job, at the ripe age of 25, was to lead the global expansion efforts for the new consulting line that had formed after the acquisition of my previous company, Übermind.

During this acquisition, I was lucky enough to be given the opportunity to avoid the traditional consultant paths offered by Deloitte, which may have been interesting, but likely would’ve sent me down a completely different career trajectory—a career with more suits, planes, and hotels next to the airport. Instead, I was lucky to be offered a global expansion role, which kept me out of client-specific consulting, and made me an internal operator, tasked with launching and growing the newly-formed Deloitte Digital Studio Model. My role in global expansion had some interesting requirements, which ultimately led me to my first remote work experience. These included:

Time zone management. As you might imagine with the word ‘global’ in the title, my job entailed working with teams and people in different countries. This meant having to manage time zones outside of my usual +/- 3 hour calculations.

Video and conference calls. For years, most of my meetings were in person. Whether it was in the office with my studio coworkers or meeting a client to present, my time was spent literally face-to-face. And then one day, that all changed. I went from mostly in-person, to mostly virtual. I didn’t feel it immediately, but over time, it felt like my personality shifted from being a real person to a virtual person.

Isolation. In the shift to virtual work, it meant a disconnect from my local colleagues. Even if we worked in the same office, we didn’t have the same schedule, the same work, or the same experiences anymore. I found it more and more difficult to talk with them about work, since our worlds were so far apart. Eventually, I stopped coming into the office except to socialize or for the occasional office-sponsored happy hour.

After a decade of working remotely, I’ve realized that there are things I deeply miss about working in an office. I don’t think I’m completely alone here. In fact, just the other day, a past colleague of mine told me they’ve accepted a hybrid role. They’ve been working and advocating for remote work for years, and yet, they decided to take a little break from the fully-remote world.

As someone who has spent a lot of time thinking not just about how we work, but how we are productive, how we cultivate a relationship with work, and how we set boundaries, I think there are gaps that have yet to be filled in remote work. A growing body of research underscores the profound impact of social interactions and environmental context on our work and well-being.

I want to be abundantly clear: I do not want to return to the office, not now, not ever. Further, I don’t believe in-person work is a better way to work, at least not in most cases. But more importantly, I think the remote/in-office debate leaves little room for nuance, and therefore misses the mark altogether.

I’ve realized that there are some important things I am missing when working remotely, and I plan to fix them in 2024. And no, it’s not the ‘random coffee chats’ or ‘in-person’ meetings.

Scheduled social interactions - again, not the random chat kind. What I miss is the scheduled social interactions of office timelines. I miss the ‘let’s grab lunch/coffee’ times of the day. When we have scheduled social time, we naturally increase our productivity in order to ensure it doesn’t interfere with our social mores the scheduled social time. When our schedule becomes flexible, we lack the urgency of fixed deadlines, even if they’re for social interaction.

Time offline - I miss the forgiveness and empathy of needing time outside of work. The ability to say, ‘hey, I’m on my way to the office, I’ll look at that when I get in.’ I miss the option to say, ‘I have to leave early to run an errand, so I won’t be able to make a 4pm meeting today.’ I find that, as a remote worker, it is incredibly difficult to share the reasons that we can’t—or won’t do things. Worse still, remote workers are often given very few options to not work. The assumption is that by giving up the commute, you have infinite time to work, and therefore should always be online.

Thinking time - the commute is shit, but it can have benefits. First and foremost for me: time to think. One of the first things that I realized I was missing about the office was time to be alone, gather my thoughts, and think about things that were on my mind. By removing this time, I’ve found that I default to action. Instead of sitting and thinking about an idea on my commute, I choose to work. Instead of taking time to breathe, I work. Everything gets flattened to work.

A sense of place - how we feel about what we do is incredibly important, as it shapes our self-worth and helps us orient ourselves to the world. Where we do what we do can be just as important. One of the biggest challenges of working remotely is being able to place ourselves in work mode. When you can work anywhere, we see work everywhere. But the office gives us a place to place work. It lives there. It stays there when we leave. It has a home, and it’s not our actual home.

All of these are specific to me. It doesn’t mean that they are insurmountable, or something that changes the calculation of my interest in working remotely. In fact, they further cement my position on the subject, as they reinforce the idea that remote work isn’t just about where you do your best work, but how you do your best work. If we want better ways to work, we have to think outside the box and explore all ways of working and living in harmony. I want reinforce this in my own work and in the narrative at large.

Rethinking My Office

In 2024, I’m taking a different approach to working remotely. I’m keeping the core components; working asynchronously, documentation-first, (mostly) virtual meetings, etc. But I’m also making some pivotal adjustments that I think will have a major benefit for me, my work, and my family.

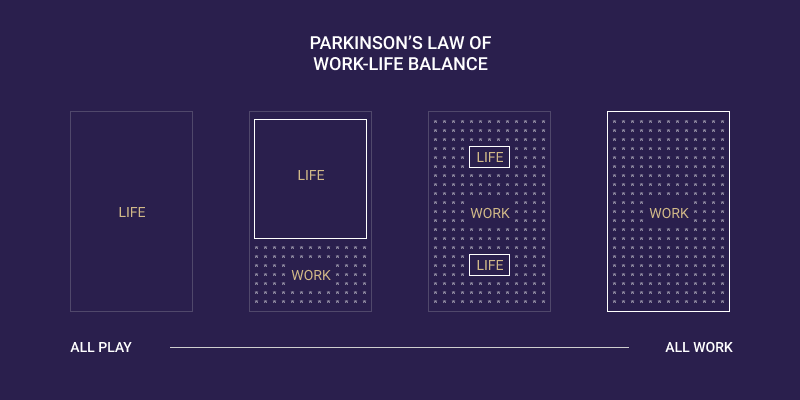

Be a 9-5er - I’m a huge fan of work-life harmony, no matter how you come by it. Historically, I’ve leaned into my natural rhythms of being a cycler, but over time, I find it wears on me. Instead of working when inspiration strikes or I feel ready to tackle something, I just end up grinding through work, all day, with micro-breaks. For 2024, I’m taking a stronger stance on remote work boundaries, and trying a 9-5 schedule—or as close to that as reasonable.

Co-work - with our recent move back to Seattle, I’ve decided to pick up an office at a co-working space. Luckily, it’s right next to our home, so the commute is the time it takes to ride the elevator down, walk 50 yards through our garage, and ride a second elevator back up two floors. This setup allows my wife to have her own space at home, and helps me enforce my goal of being a 9-5er.

Go analog - one of my challenges with remote work is the fact that everything goes through my screens—from my phone to my laptop to my desktop, it’s all screens. Passing thoughts, ideas, and chats through this glass box filled with pixels isn’t the way I want to exist, and it’s not how I’ll do my best work. To combat this, I’m integrating analog tools into my workflow, including a whiteboard, notebook(s), and a separate, analog desk.

Walk it off - I need to walk more. When I was in the office, I’d walk a lot more. I’d go to lunch, get coffee, or just do a walking meeting with people from the office. While most of the time those walks happened with close colleagues and friends, that wasn’t always the case. Sometimes I’d join a random group of designers or engineers, just to get out. It’s hard to do that on your own, but I want walking to be a part of my life. So every day, I take my dog across the street for a walk. Some days, I walk my wife to work. Others, I walk to meet someone for coffee, lunch, or drinks. My goal is to walk as much as possible.

Zooming Out

Depending on your stance, these changes may sound mundane or revolutionary. Remote purists may even take issue with some of these. But that misses the point. The point of remote work has never actually been about working at home, on your couch, or on a beach in Fiji. Remote work is about flexibility. It’s about a way of working that not only helps us do our best work, but bring work and life into harmony. And the harmony of work and life can only be heard when we listen and adjust our tone.

It’s easy to look at what we don’t have and assume it’s better.

We have the Honda, but we want the Tesla.

We have the big house, but we want the boat.

The grass, perpetually seems greener, no matter the context.

In reality, the grass isn’t always greener. Sometimes, the grass is greener in a few spots, and dead everywhere else. We might only see the small patch, and assume the rest looks the same. The map is, in fact, not the territory.

Our workspace choice shouldn’t be binary.

We shouldn’t have to choose between a sub-par home office (aka kitchen table) or a high-rise office.

We shouldn’t have to choose between working a job we like, and spending necessary time with our family.

We shouldn’t have to be forced into these polarities—there exists space for convergence.

When it comes to remote work, it’s easy to feel like we need to pick sides; you’re either with us, or you’re against us. Like anything else in life, we should admit and embrace the need for better options, both in work and at home.

The Delphic oracle might have been speaking to workers when she famously said, "know thyself.” I, for one, plan to do so.

You Don’t Need Moderation

Work, Creativity, and the Fallacy of Restraint

Every Monday morning, I sit down at my desk, turn on any Tycho album, pull out my trusty notebook, and plan my week.

This little daily ritual keeps me focused and grounded.

It’s something I try to stick with every weekday, because it helps me avoid overcommitting to too many meetings, too many to-dos, too many agreements.

But recently I realized something: it doesn’t actually work.

Well, it works, but not as intended.

I know this, because I finally sat down and looked at the data.

As one of those OCD people who tracks their time, manages an overly-complex Notion workspace, and uses best-in-class productivity tools like Sunsama and Rize, I have the data.

At the beginning of each new year, I reflect on what I’ve accomplished in the last twelve months and what I’d like to tackle in the coming year. During this practice, I evaluate not just how much I completed, but how I felt about what I completed, and how much effort it took to complete everything.

This year, when I looked at my stats, they were pretty staggering. I’d worked an average of 50-60 hours each week, taken 2-3 weeks off, and only completed 60% of the goals I’d set out to accomplish at the beginning of the year. All in all, it didn’t look great. And yet, my feelings told a different story.

I felt accomplished.

I felt energized.

I felt ready for more, not less.

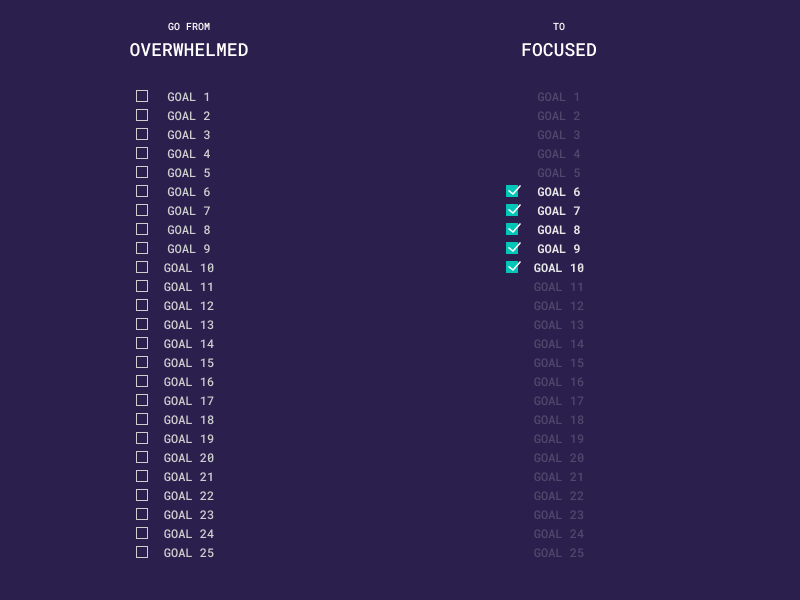

For most, the outcome of a process like this leads to a goal of working less, scaling back, or finding ways to optimize. And I’ll admit that, for most, this is the right outcome. I’ll play along with the typical work-life balance narratives that even I espouse on a regular basis. Yet, when it comes down to it, my ambition won’t rest. The list of objectives for the coming year just gets longer and longer. And before you tell me about the 80/20 rule, Buffett’s 5/25 rule, or any other prioritization framework, know that I both know these and still find myself in the same situation.

Because, the truth is:

I willingly overstretch myself.

On any given day, I find myself toggling between:

two monitors

three books in progress

dozens of article or newsletter drafts

hundreds of open browser tabs

thousands of ideas

For me, chaos breathes life into an otherwise mundane existence.

In fact, managing the chaos often feels like a dance does.

You can learn to dance by following step-by-step instructions; right hand on your partners shoulder, step forward with your left foot, slide your right foot across…and so on. Or, you can watch someone dance and find your own groove. Instead of resisting your natural flow, you can learn to embrace it and move with it.

If you are resisting something, you are feeding it. Any energy you fight, you are feeding. If you are pushing something away, you are inviting it to stay.

— Michael Singer

My fragmented, overworked, chaotic existence goes against all conventional productivity advice and breaks all norms. Most people simply cannot understand how—or why—someone would be a willing participant in such circumstances, especially when it comes to work. We’re willing to accept and embrace a lack of moderation when it comes to particular hobbies, passions, religion, and so many other aspects of modern life.

And yet, when it comes to work, the modern narrative tells us to cut out as much as we can.

Like sugar, work is best consumed in small doses, only when necessary.

While work might produce a nice, temporary high, enjoy too much and you’ll crash.

Or at least that’s what we’re told.

But creative work is different. And makers of all kinds — painters, artists, musicians, etc. — often find that creativity blurs the line between what is considered work, and everything else. Putting artificial constraints on your creative brain, telling it to turn off, rarely works.

Constraints are incredibly powerful tools for creativity. But creativity and innovation aren’t always about limitations. In fact, creativity and innovation often come from connecting disparate ideas or concepts. As David Epstein points out,

Modern work demands knowledge transfer: the ability to apply knowledge to new situations and different domains.

The transfer of knowledge and the ability to apply it across different domains requires expansion, not contraction. The constraints of typical productivity advice turn moderation into frustration. Which is exactly why I choose to accept life without moderation.

Where you see chaos, I see creativity.

Where you see obstacles, I see opportunities.

And, when it comes to work, my brain wants more.

As I wrote in 2020, I think this is crucial for most people to find ways to do the minimum amount necessary to get the most monetary value for themselves. It’s the most logical way to approach anything so transactional: maximize ROI.

But the I in ROI isn’t the same for everyone.

I’ve come to realize that moderation just isn’t for me. And it’s not easy, but nothing in life is easy. Instead of fighting it, I’ve learned to harness it and use it to my advantage.

Accepting and integrating chaos might be the fastest way to find the signal of creative inspiration. Whether it’s work, a hobby, a book, or a creative endeavor, keeping your momentum is the key. If you let doubt or fear stop you, it just might bring all other creative outlets to a screaming halt. Take on more than you think you can handle, and see where each permutation takes you.

Munger's Laws

10 Basic Rules Charlie Taught Me About Legacy

Charlie changed my life.

I felt I knew him, even though I didn’t.

With words alone, people have the power to engrave.

At 25, I discovered Seeking Wisdom in 2015, and it was all I needed to be a lifelong Munger follower.

I devoured every book, interview, and speech that featured him. I left no stone unturned when it came to studying the works of this great thinker, spending countless hours writing his quotes and ideas into my notes. I guess I hoped that capturing them would someone embed them so deep in my subconscious that I’d slowly become a little like Charlie.

And in some ways, they did.

I learned to sit with my thoughts long enough to realize how bad they were.

I learned to keep things simple, even when it didn’t feel right.

I learned that nobody is learning from the greats—like Munger—is an art.

Though I learned a lot about finance, investing, and mental models, something quite different stuck with me as I got older.

It wasn’t the reflections and insights that stayed with me, but Munger’s inevitable legacy.

When I was younger, I didn’t think about legacy. I focused my thoughts and energy on the now, trying to do as much as possible with what I had before me.

As time passed, I started to think more about legacy. I saw how great leaders, thinkers, artists, and creators reshaped the world, and left a mark. Even after death, the legacy lives on.

Munger’s legacy became more apparent and essential after passing away in 2023 because the insight machine that is the mind of a great man had been discontinued. We couldn’t get just one more quote or idea. That was it, the end.

But that’s what makes a rich, profound legacy like Munger’s so unique—we can relive it and continue to build on it. We can continue to learn and grow alongside his work, as I did when I was 25, devouring every word and idea he shared with the world.

My fascination with legacy stems from the dialogue it creates with the past, present, and future versions of me. Thinking about your legacy can be self-absorbed, or it can be motivating. I find when I think about it, it’s not with the lens of trying to do something to impress anyone. Instead, I remind myself that everything I do will be part of my legacy, for good or bad. In that way, it is up to me to decide what to do with my time.

Do I choose to contribute in a way that cements a legacy I would be proud of?

Munger’s work was the early inspiration for Path Nine, which became my humble attempt to build and cement a legacy of my design and thinking. Munger’s unwavering character, intelligence, honesty, humility, and professional success fueled my imagination and motivated me not just to work but also to think better.

The Munger Legacy

Great thinkers are rare.

Charlie Munger was the rarest of the rare.

He was the black swan of modern thinkers.

As I wrote in Eat a Bit of Candy,

Munger saw life with a lot of clarity. He’s a thousand-yard stare in human form; focused, precise, resolute.

Munger was the right-hand advisor to the infamous and equally brilliant Warren Buffett. Where Buffett was best known for his financial success and avuncular attitude, Munger was known for his worldly wisdom and insight. No matter your experience or background, you'll likely gain something from the insights he shared across his 99 years of calculated, thoughtful, and intellectual rigor. Unfortunately, we lost this great thinker in 2023. Upon passing, countless writers, thinkers, influencers, business leaders, tech bros, and finance execs posted their thoughts, noting Munger's impact on their lives. And before the dust settled on the digital obituary, the listicles and roundups came flying in. If you're so inclined, here are a few:

6 longevity tips Charlie Munger believed in for a long and happy life

17 Charlie Munger quotes that teach us invaluable lessons about investing and life

Most of the memoriam posts about Munger focus on some of his most influential insights and quotes, partly because it's the easiest way to pump out an article that gets clicks (we all love an easy win, especially if it requires minimal thought and work, for that matter). Yet, for everyone I read, I grew more and more disconnected from the richness of this thinking. A series of quotes can be interesting, but it robs us of the depth we long for and associate with great thinkers. Ironically, most of what was written and shared was antithetical to Munger's belief that everyone isn't just handed cheap, easy wins.

I believe in the discipline of mastering the best that other people have ever figured out.

He was a man who somehow existed inside and outside of time's bounds. His wisdom wasn't some cheap tweet or cursory thought pulled together for a soundbite. His thoughts were deep, nuanced, and colorful. His advice wasn't meant to be advice but to communicate a more profound truth. Munger's currency of choice wasn't advice; it was wisdom.

And that made him different—a constant pursuit of capital-T truth.

He wasn't overly concerned with being well-known despite his massive success.

Despite having millions of devotees, he focused his time and energy on something other than showmanship.

He focused on mastering the best of what other people already figured out.

And his pursuit of mastering the best rings loud in my ears.

So, instead of regurgitating Munger's thoughts, I decided to go deep and summarize his thinking into a précis, or a summary of the anthology of Munger.

This piece is my attempt to curate and synthesize 99 years of next-level thinking to serve as a pairing-down of a seminal body of work. It's not meant to be a comprehensive breakdown of Munger's work—there are books for that, after all (Poor Charlie's Almanac, etc.)—but rather a dilation of the lens with which we view and embody his work.

In the process of endlessly digesting Seeking Wisdom and Poor Charlie's Almanack, watching "The Psychology of Human Misjudgment", and devouring every article I could find on Munger, I stumbled upon natural groupings that define this anthology. These are what I call "Munger's Laws."

Laws that uphold his wisdom.

Laws that remind us of his character, intellect, and generosity.

Laws that, above all else, cement his legacy.

Law 1: Avoid stupidity

It is remarkable how much long-term advantage people like us have gotten by trying to be consistently not stupid, instead of trying to be very intelligent.

We recognized early on that very smart people do very dumb things, and we wanted to know why and who, so that we could avoid them.

In life, our primary law should be geared toward the idea of avoiding stupidity. It’s an evolutionary concept that goes back to the earliest days of every living being. You must avoid what could take you out of the game to survive. As Munger once said,

All I want to know is where I'm going to die, so I'll never go there.

At work, most of what we aim to do is to look smart, when in reality, we’d be better off if we tried to avoid stupidity. If you look at some of the most successful people, they’re rarely the smartest or even the most qualified, at least in a traditional sense. During his commencement speech at USC law school in 2007, Munger stated:

I constantly see people rise in life who are not the smartest, sometimes not even the most diligent, but they are learning machines. They go to bed every night a little wiser than they were when they got up, and boy, does that help, particularly when you have a long run ahead of you.

Dropouts like Thomas Edison, Mark Twain, and Steve Jobs all found success via non-traditional pathways, by simply putting their head down and focusing on getting a little better each day. Reflecting early and often is one of the best ways to avoid stupidity. Though some things are complicated, only some things should be.

Law 2: Embrace the power of compound interest

Everything starts small. But compound interest turns small things into massive things; it just takes time. Compound interest is a powerful concept that can bring immense benefits to our lives. It helps us earn not only on the initial amount invested, but also on the accumulated interest. Munger knew this like the back of his hand, and he saw how it impacted everything around him, from investing to the growth of every living organism—he saw it everywhere.

Understanding both the power of compound interest and the difficulty of getting it is the heart and soul of understanding a lot of things.

But, as he points out, our ability to comprehend the power of compound interest holds us back from making better decisions. Whether it's in finance or other areas of life, we can leverage this power law to achieve greater growth and success. By continuously learning and combining our skills, we can accelerate our progress and achieve remarkable results. Just remember what Charlie said,

I think that a life properly lived is just learn, learn, learn all the time.

Law 3: Allocate time to think

We pride ourselves on our ability to do. We use phrases like “bias for action” and “be proactive” to describe and encourage people to dive headfirst into something, putting thinking aside. As someone who studied architecture and spent the early days of my consulting career thinking, I’ve always found this to be counterintuitive and, at times, counterproductive. You can’t just start building a house and figure it out as you go. You need plans, details, drawings, annotations, and coordination—all things that require thinking.

Neither Warren nor I is smart enough to make the decisions with no time to think.

In his article “In Defense of Strategy,” Packy McCormick does a fantastic job articulating the value of strategy and thinking. The art of clear thinking doesn’t come from the unpracticed; it comes from those obsessed with exploring the depths of their mind, expanding boundaries, pushing limits, testing ideas, and, most importantly, creating space. Only once we have opened up space and time for thinking can we roam the land without restriction.

If you want to be a good thinker, you must develop a mind that can jump the jurisdictional boundaries.

Law 4: Stay grounded

When starting my first company, one phone call left a lasting impact on me. I met with a fellow founder who had just sold their software company to a mid-sized tech firm in Seattle. What struck me was not the shared insights or advice but the arrogance I felt dripping off every curt and cryptic reply. Though I was still a young entrepreneur, I swore that no amount of money would ever change me, or my ability to be kind and helpful. And it goes to precisely what Munger would say,

Remember that reputation and integrity are your most valuable assets and can be lost in a heartbeat.

Success shouldn’t change you. Find a way to stay grounded.

Law 5: Create systems for success

Munger is both a complex and a simple thinker. Like Buffett, he embraces the simplicity of checklists, and also the complexity of a lattice work of mental models.

No wise pilot, no matter how great his talent and experience, fails to use his checklist.

It's so easy to get so busy you no longer have time to think. The price of not thinking clearly is relatively high, albeit sometimes delayed. But when it comes to designing a life and a career, it’s important to remember that we need systems to help keep us accountable. Or, as the infamous James Clear puts it, “You do not rise to the level of your goals. You fall to the level of your systems.”

I think about this a lot. Every day, I look at what I’ve accomplished and try to find one optimization—one way to turn a manual process into something scalable, repeatable, and easy to follow. I don’t do this to simplify work, but to maximize space for creativity and deep thinking. It’s my way of looking for patterns that keep me on track and push me toward a more successful version of myself.

You’ve got to have models in your head. And you’ve got to array your experience—both vicarious and direct—on this latticework of models.

Law 6: Stick with what works

Every week, I read a post on Reddit or Blind asking, "What is the highest-paying job in tech?" Inevitably, these questions are commonplace on platforms that promote financial success as the critical metric for a well-crafted life and career. We should expect no less from a society that cares little about the creative, alternative forms of success that often create the most fulfilling lives and careers. But we certainly shouldn't embrace it.

The problem with these types of questions is that they rarely lead to a successful career. Say you decide to be a doctor because it pays the highest salary, what happens when your passion dies out or you lose the motivation to keep moving?

What happens when lifestyle creep catches up to you, and you get stuck in a system you hate?

What happens if it causes everything else in life falls apart, and your family leaves you?

You’ll do better if you have passion for something in which you have aptitude. If Warren had gone into ballet, no one would have heard of him.

The realities of a life and career well-crafted are that they require the delicate intertwining of passion and aptitude; your interests need to meet your skills. It doesn’t need to be a 50/50 split but involves integration. The sooner you realize that moving interests and skills closer together in the Venn diagram of life, the sooner you’ll find yourself in a place that few can replicate, but many will attempt to emulate.

Law 7: Choose a path, and accept it

Starting a new business, building a new career, or doing something people don’t understand well or that doesn’t fit into a nice, neat box are all high-risk, high-reward paths in life. But they’re filled with triggers for self-doubt, imposter syndrome, and frustration. All paths are hard, it’s a question of what kind of hard you choose.

Whenever you think something or some person is ruining your life, it's you. A victimization mentality is so debilitating.

At some point, we have to chin up and move forward. Life gets hard, fast. As I look back on the adversity I’ve faced in starting, growing, and building companies, it’s easy to be overwhelmed by the challenges and frustrations faced along the journey. Yet, at the end of the day, each has made me better, and therefore made me stronger. For every mistake I made, I found two news ways to improve on that in the future. No matter how bad things seem, there is always a way through it, and a victimization mentality isn’t a solution.

Law 8: Avoid mediocrity

Most creative people are cursed with a distinct kind of pain: the pain of optionality.

Being creative often leads to multiple ideas, at times in rapid succession. It’s easy to get excited and distracted all at the same time. There are many things to pursue, and the creative brain sees opportunity everywhere. But without limitation, we risk sending ourselves into a death spiral of projects and ideas that never exceed 10% completion. As Ned Rorem once said, “It isn’t evil that is ruining the earth, but mediocrity. The crime is not that Nero played while Rome burned, but that he played badly.”

And Munger reminds us of the same pains and pitfalls of mediocrity, saying:

It takes character to sit there with all that cash and do nothing. I didn't get to where I am by going after mediocre opportunities.

In Thriving with Limitation, I shared the creative limitation that artist Pierre Soulages, "the painter of black and light," was known for creating some of the most fascinating, minimalist, abstract art in the 20th century. He often felt overwhelmed by choice — materials, colors, subjects, it was all too much. In 1979, he made the radically divergent choice to reduce his palette to one hue: black. We can learn a lot from Soulages. Whether you’re thinking about starting something, building something, or continuing something, constraints are a way to keep you grounded—they allow for and breed creativity.

Law 9: Learn to rise

Those who keep learning, will keep rising in life.

The first step to rising is realizing we can evolve—we're capable of change and maturation. Munger saw mistakes as the leavening agent in human maturation, providing the necessary conditions to encourage and facilitate intellectual expansion.

I like people admitting they were complete stupid horses’ asses. I know I’ll perform better if I rub my nose in my mistakes. This is a wonderful trick to learn.

We must first face ourselves, before we can really face the world.

Forgetting your mistakes is a terrible error if you’re trying to improve your cognition. Reality doesn’t remind you. Why not celebrate stupidities in both categories?

Mistakes are part of growth. Learn from them. Don't forget them. Instead, reflect and move on.

Law 10: Keep life simple, and minimal

One of the greatest ways to avoid trouble is to keep it simple. When you make it vastly complicated—and only a few high priests in each department can pretend to understand it—what you’re going to find all too often is that those high priests don’t really understand it at all…. The system often goes out of control.

We have a passion for keeping things simple.

We have three baskets: in, out, and too tough… We have to have a special insight, or we’ll put it in the too tough basket.

Simplicity is something I just recently understood. When studying architecture in college, I remember a long and detailed discussion with a professor about the differences between simplicity and minimalism and their relative importance in architecture. To the best of my recollection, the argument went like this:

Simplicity = bad.

Minimalism = good.

And from that point forward, I only referred to anything in architecture as minimal, never simple. But as I recall, the point was slightly more nuanced and focused on minimalism as a stripping down of elements. Conversely, simplicity resulted from an underdeveloped idea requiring more analysis and study, leading to a less considerate design.

Architecture lessons aside, simplicity is my north star when it comes to decision-making. My gut usually knows the answer, and my brain tries to convince my gut that it knows nothing. Of course, I’m always an advocate for Second-Order Thinking and in-depth critique, but sometimes, they can stand in the way of what would ultimately be a straightforward decision.

If something is too hard, we move on to something else. What could be simpler than that?

Learning as a Pathway to Leaving an Everlasting Legacy

For all his profound wisdom, Munger was nothing more than a man.

He sweat, bled, cried, laughed—and ate a bit of candy.

His wisdom lifted me and kept me planted firmly on the ground.

His fingerprints are all over my work and my life.

He left a mark.

Though imperfect, Munger’s laws provide foundational principles that can be passed down from generation to generation. These laws are a great place to start if we wish to think, work, and live better in the next 99 years. He was incredibly thoughtful, successful, and yet entirely grounded—and that’s exactly how I want to be remembered.

"Do not seek to follow in the footsteps of the wise, instead, seek what they sought." —Matsuo Bashō

That’s how he beat the market, outlasted the competition, and built a legacy.

Had he not been a billionaire, he’d still be successful.

Because the man, his morality, and his modus operandi surpassed the heights of his fortune.

His legacy lives on.

Things You'll Never Regret

Loss as a Reminder of the Depths of Life

Nature's palette on full display, vibrant colors adorning the Amalfi coast after a magnificent storm.

“If today was the last day of my life, would I want to do what I’m about to do today?”

It's difficult to fathom the pain outside our limited existence. We are the thinking, feeling, and suffering centers of our universe. Pain, pleasure, gratitude, pride, anxiety, fear, loneliness, regret; each constitutes the best and worst parts of being a human.

In times of struggle, it's helpful to remember that we all feel the same.

Recently, I lost a friend in a tragic accident. He wasn't a close friend, but proximate loss is a tragedy regardless of relationship. The loss—and my processing of it—forced me to evaluate what matters most to me and how I can live a life that honors my values. This isn't a tribute to our friend—he deserves much more than I can write about him. This is a reflection for those of us who wish to live and explore a life without regrets.

Losing anything can serve as a catalyst for change. I personally felt challenged to think critically about where and who I spend my time with. So I asked myself, "What experiences and activities can I do that I will never regret?"

The answer that's beaten into our heads over and over is that, on your deathbed, you'll never wish you'd worked more. But if regrets are simply answers to the question, "What did I want for myself that I didn't allow myself to have?" work might make the list. While there are clearly many things that should make the list, work shouldn't be exiled because that's what we're taught to think—that work is unimportant.

Who we are is a complex tapestry of seemingly innocuous acts that propel us through the universe. Work is a thread that weaves its way into the tapestry, adding color, complexity, nuance, and strength. Frequently, it's a mechanism for meaning and self-esteem. Like it or not, the thing you spend more than 50% of your life doing and focused on (i.e. work), is important.

In both work and life, we're faced with challenges. But worse still, we're handed invisible scripts that we're expected to follow mindlessly. These scripts come from our friends, parents, teachers, colleagues, neighbors— everyone and everywhere. Scripts that tell us to:

take the well-paying job (even if you hate it)

buy the house in the suburbs (even if you don’t want to)

climb the corporate ladder (even if it destroys your family)

have a few kids (even if you’re not meant to)

And on and on…

For some, they help usher us onto a path of prosperity; they lift, motivate, and encourage.

For others, they hold us back; they oppress, infuriate, and repress.

For my friend, and for many, work isn't the top priority. But I bet if asked, many people would say that work plays a significant role in their lives because it partially enshrines their legacy. Work contributes to self-worth because what we do is often conflated with who we are. While my friend may have regretted certain elements that centered around work, I suspect he wouldn't change it, for it gave him and his family the life they enjoyed together. It built a foundation for his energy. It made up or unlocked a part of him. He built a life not around work, but with work.

He owned a family business and ran it, in part, with the help of his family. Not only was he building a business, he was building a legacy, in his community, his family, and himself. His work was a part of him, not a means to an end. And this is where the confusion lies: in our ability and inability to find the genuine connection between work and living.

For me, work isn't just about laboring or making money; it's about doing something I won't regret. Writing this newsletter is work, but it's work I won't regret. While work may or may not fill the same space in your life — maybe it's your kids, your family, your hobbies, your pets — these things add up to the sum we all want: a life worth living.

Our work may not be the ultimate representation of our existence, but for many, it represents us in ways that are often indescribable: our ambition, energy, ideas, motivations, and legacy. It can open the door to new relationships. It can help you find balance and safety when things go wrong. And, if nothing else, it can be one way to live a life without regret.

“Has this world been so kind to you that you should leave with regret? There are better things ahead than any we leave behind.”

Like Mr. Lewis, I won't presume your like is devoid of regret. No one should. Life isn't about living without regret; it's about minimizing the regrets that you have control over. Failure is not allowing yourself to experience the thin line between a well-lived life and a life without regret. A life well-lived inevitably leads to the potential for regret, but at the end of the day, it comes down to the type of regret you're willing to accept.

Here is a list of fifteen things that you won’t regret:

Staying out too late laughing with close friends

Dropping whatever you’re doing to help a friend in need

Spending a little extra on the activities that bring you joy

Sitting down to watch the sun set

Holding the hand of someone you love

Standing up to injustice or oppressive forces

Pushing physical limits and doing just one more rep at the gym

Taking five minutes to meditate and breathe

Stopping to give extra cash or change to a person in need on the street

Putting every ounce of energy you have into that project at work

Sending a “just checking in” text to a friend or family member

Saying “no” to another meeting or request for your time

Waking up early to go for a sunrise walk/hike/ride/swim

Taking that ‘once in a lifetime’ trip with people you love

Taking a leap and betting on yourself

Like it or not, we're all faced with the realities of a finite existence. And while many details in our lives are unknowable and unchangeable, we're sometimes presented with opportunities to turn mundanity into miracles. Life simply cannot be lived without regret. Instead, the essence of life lies in minimizing regret by seizing opportunities, learning, growing, and embracing the depths that life has to offer. We have the power to make choices that we will never regret—and I hope, like me, you find a way to make that happen.

So, what is it that you should do?

What actions, experiences, and contributions will bring you everlasting fulfillment and leave behind a legacy?

Like me, you may find that your work and life endeavors answer the question, "What experiences and activities can I do that I will never regret?"

And if they don't, it's time to re-evaluate.

Thriving with Limitation

The value of self-imposed constraints in a limitless world

Pierre Soulages didn’t care about earning a living. For him, life was about living—and that meant painting. As an artist, he saw possibility where others saw problems. And we can all learn a little from him.

Soulages, known as "the painter of black and light," is a world-renowned French artist known for creating some of the most fascinating, minimalist, abstract art in the 20th century. Soulages's work, associated with the "Art Informal" movement, has garnered comparisons to esteemed artists like Rothko and Morellet. His artwork commands prices ranging from millions to tens of millions of dollars. He's well known for the monochromatic palettes he uses to evoke a sense of depth, energy, and mystery in his artwork. But what's most impressive is not his education, background, or early work — it's his approach.

As a young artist, Soulages found the business of art quite complex. He often felt overwhelmed by choice — materials, colors, subjects, it was all too much. In 1979, he made the radically divergent choice to reduce his palette to one hue: black. He coined this style "outrenoir" or "beyond black" to simplify his work and set him on a path as a renowned artist.

His extreme discipline gave him endless freedom.

Harry Cooper, the director of modern art at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, once said that Soulages "thrived with limitation," by deliberately limiting his color palette. Instead, he directed his attention to the remaining elements: "Light, texture, scale, shape, direction of stroke."

He became a master of self-imposed limitations.

Rather than overwhelming his canvas with countless possibilities, he adhered to constraints that enhanced his creative focus and discipline. These limitations challenge him to push the boundaries of his chosen elements and techniques, resulting in his work's distinctive and influential aesthetic. The limits didn’t hold him back; they set him free.

We can learn a lot from Soulages. Whether you’re thinking about starting something, building something, or continuing something, constraints are a way to keep you grounded—they allow us to thrive with limitations.

The Value of Constraints

At work, school, and in life, we’re told to push boundaries and think outside the box. But creative thinking requires a certain amount of practicality, or at least a connection to reality. We need the box to think outside of it.

This was one of the first lessons I learned while studying architecture.

When receiving prompts for architectural projects, designing something interesting, unique, or fun was easy. But without constraints, the design was nothing more than a concept. Building codes, budget requirements, zoning, etc., all interfere with the creative process. But over time, I learned that the constraints forced me to think more, be better, and push myself.

We’re all working with constraints, and the most creative leaders and creators understand that constraints are a helpful hurdle, not a burden. Constraints help us in many ways, including:

Focus: constraints act like bumpers on a bowling alley lane; they keep you from going off track. By defining boundaries, you eliminate distractions and are forced to find solutions within your constraints instead of wandering aimlessly.

Creativity: paradoxically, constraints fuel creativity. Constraints require us to stretch our minds to find creative solutions or unconventional approaches to break through our limitations. Further, they force us to be more resourceful and inspire innovation.

Consistency: not only do constraints drive creativity, they also enforce a certain amount of consistency and efficiency. Limiting your palette reduces the potential distractions that inhibit your ability to focus on what's important.

Uniqueness: it's harder to stand out when everyone uses the same tools. Creative expression is enhanced by the limited factors in colors, materials, techniques, voice, etc. Constraints help shape identity.

Growth: constraints—those dauntless companions—beckon us to embrace new skills, capabilities, and mindsets. In their audacious grip, our minds stretch to unfathomable horizons, enabling us to ascend to loftier summits of accomplishment. Thus, through these very constraints, our potential for growth blossoms, vibrant and profound.

Overall, constraints create opportunities for us to thrive in new ways, even if we don't initially see the benefit. They encourage exploration, ideation, focus, and efficiency, ultimately leading to better outcomes.

Optionality Limits and the Art of Self-Editing

Life's most difficult challenge is embracing our limitations without suppressing our creative capacity. Extraordinary results are forged in fire.

But learning to limit ourselves is challenging. As children, we strive for the freedom that we believe adults have; the “do what I want, when I want it” mentality. Without discipline, life succumbs to chaos. It is through discipline that freedom is found. To reshape your life, embrace the power of setting and creating limits. Here are a few lessons I've learned in embracing constraints:

Reframe Constraints to Challenges - the good ol’ "Do More with Less."

Instead of perceiving our constraints as blockers, embrace them as challenges. Leverage your ambition and determination to find creative, resourceful ways to do more with less. Maximize your effectiveness, and increase your leverage. You'll soon realize that the challenge is the goal; the outcomes will follow.

Define Hard and Soft Constraints - barriers are not boundaries.

I’ve learned to differentiate between “hard” and “soft” constraints. Hard constraints refer to fixed limitations that must be strictly adhered to, leaving no room for deviation. For example, in architecture, these are building codes and zoning requirements. These limitations define the boundaries that creators must operate within.

In contrast, soft constraints are more flexible and allow for a certain degree of adaptability and interpretation. Soft constraints are boundaries that sit outside the hard constraints, acting as a second layer of creative constraints. In architecture, these might be material and/or color palettes. If you need to, soft constraints may require some flexibility, but the goal is to keep the soft constraints in place by default.

Experiment with Lots of Ideas - not every combination works; keep trying.

Experimentation is crucial for the creative process, and artists often explore numerous ideas to uncover new possibilities. Soulages was a master of experimentation. His ability to hold onto his work loosely was unmatched. If a canvas wasn't working, he rolled it up and set it on fire in the garden. He didn’t continue with bad work or work he didn’t enjoy.

“It’s what I do that teaches me what I’m looking for.”

Soulages understood that creative exploration involves embracing both successes and failures. Creativity often thrives in an environment that encourages risk-taking. Step outside your comfort zone and be willing to take calculated risks within the constraints. Embrace the opportunity to push boundaries, challenge conventions, and explore uncharted territory.

Explore Collaboration and Diverse Perspectives - get out of your own head.

Engage with others and seek diverse perspectives when faced with constraints. Collaborating with different individuals encourages fresh ideas, unconventional thinking, and varied skill sets that help overcome limitations and stimulate creativity.

Remember, creativity flourishes when we have to navigate within limitations rather than having complete freedom. By reframing constraints as catalysts for innovation, you can harness your creative potential and transform limitations into a springboard for original and imaginative solutions.

Whether you're running a business, creating content, managing a team, or just trying to live a more fulfilling life, constraints are the filtering mechanisms in a chaotic world. There's always too much information. We're constantly bombarded with content, data, and ideas — life is a flood of information. We lament the abundance of choice and loathe the lack of focus. Our job, if you will, is to learn to limit—to limit:

what we pay attention to,

what we spend time on,

what we absorb,

what we worry about,

what we need.

Soulages realized that where some see black as the absence of color, he saw a way to focus, innovate, and challenge. The color black represented the absence of the unnecessary, reducing the unnecessary. The color black presented an opportunity to be an empty vessel, lacking the hues that imbue specific meaning or direction. It's untainted and undisturbed. It is the work that gives it color.

How can you find ways to give your work color?

How can you use constraints to illuminate the work of your life?

How can you find the light within the darkness of a clouded mind?

If you could only paint three strokes, what would you paint?

Pierre Soulages, Walnut shell on paper, 1949

Searching for Places of Possibility

Threads and the Promise and Peril of Online Networks

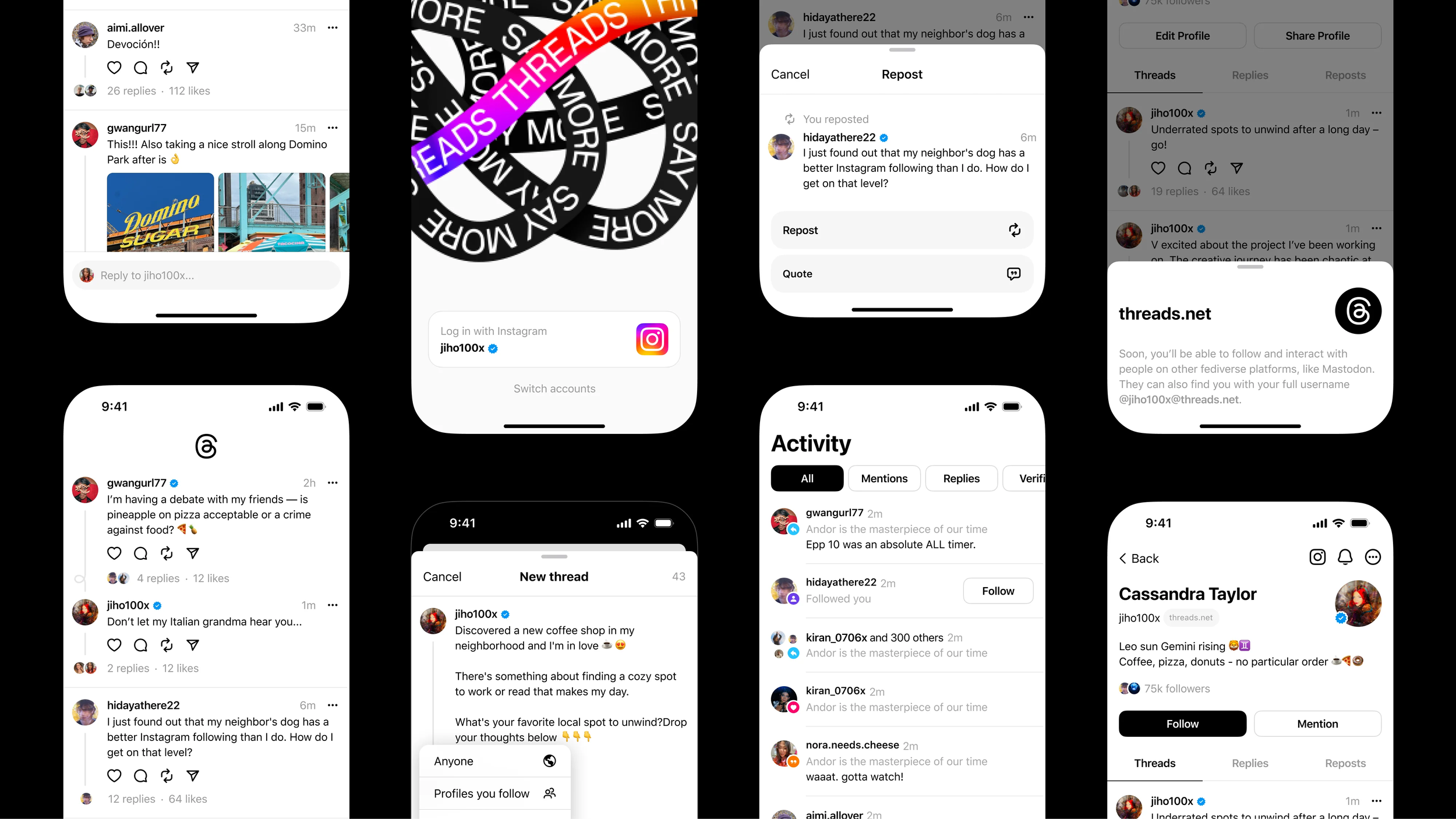

This week Meta, the parent company of Facebook and Instagram, released a new app called Threads.

It’s just like Twitter, except it’s Meta.

So that’s clever (I guess).

But here's the thing: people are enamored by it.

Meta Threads App

Meta Threads App

Here are a few quick stats to reiterate that highlight this point:

70 million sign ups just 24 hours after launch

Threads becomes the most rapidly downloaded app in history

Instagram's new app was downloaded more than 30 million times in 16 hours

How'd it get so big, so fast? The simple answer is that they leveraged the 500M daily active users from Instagram (shocker!). Not to take anything away from the stats, but it's like getting called on stage at a concert and then telling everyone that 30,000 people came to see you on stage.

All that said, the hype made me wonder why so many people are so eager to try it?

What separates it from other attempted copies like Mastodon, Bluesky, and Substack Notes?

Now, this won't be a post about the features that each offers, their strategic value, or a detailed analysis of their market position. If that's what you're looking for, talk to the greats like Packy McCormick or Ben Thompson — I bet they have thoughts, and they'll be much better than mine.

No, this post is about (digital) networks and how we simultaneously shape and are shaped by the networks and the spaces we inhabit, online and offline. It's about the role online networks like Twitter and Threads play in modern personal and professional culture.

Before we get into all that, let’s take a step back and look at Threads.

What is Threads?

Threads is a new app, built by the Instagram team, for sharing text updates and joining public conversations. At its core, Threads is a text-based social network. Like many networks before it, Threads allows users to post text updates and content to a network of followers. Users log in with their Instagram account and post 500-character updates that can include links, photos, and videos up to 5 minutes in length.

But that's not all it offers.

Threads offers users a fresh start.

The UI is simple, clean, and, if anything, understated.

It presents the feeling of a clean room; everything in it's right place.

For the time being, it’s free from contamination. And given how toxic most networks appear, a sense of cleanliness is invigorating.

Threads offer hope and the possibility of a new future, a future that is free from the tainted, mutated, and often cringe content that we've come to relate with most other social media platforms.

Even though Threads is nearly identical to Twitter, it's unclear what Threads wants to be. When we look at the mission statements of the major social media networks, it isn't easy to see where Threads fits:

Twitter: “to promote and protect the public conversation--to be the town square of the internet.”

LinkedIn: “connect the world's professionals to make them more productive and successful.”

Instagram: “to capture and share the world's moments.”

Threads: ¯\_(ツ)_/¯. While Meta has stated that Threads is meant to be less political than Twitter, it hasn’t provided a specific mission statement.

While I planned to avoid statements and predictions about the future of Threads, I suspect it will have a strong start and may ultimately pull a subset of users away from Twitter but will eventually suffer the same fate. Early success rarely guarantees future success.

The lack of mission clarity is most concerning. Without a clear mission to guide engagement, feature development, and network development, there is only one thing left to shape the platform: people.

People shape their behavior to the norms of the people around them. Waiting to see how people act is a recipe for disaster, and a regression to the mean within the current discourse. Further, given that Threads is easier to use, I suspect the race to the bottom will happen in record time, as the adoption curve goes both ways.

For a great example of how platform can reshape discourse, peruse the content on your LinkedIn feed. Or, for those of you who wish to avoid LinkedIn at all costs, check out the curated examples found on r/linkedinlunatics to see how quickly social networks devolve cringe-worthy content factories.

As Trung Phan pointed out in his excellent essay titled Why is LinkedIn so cringe?, every social network has issues:

Facebook (misinformation), Twitter (trolls), Instagram (fake) etc. Compared to these other platforms, "cringe" is probably not the most pressing concern."

And while I'm hopeful that Threads can avoid the gravitational pull of this type of content, the lack of a clear mission statement leaves me feeling concerned, especially considering the role that online networks play in binding us, personally and professionally.

What’s clear is that Threads is subconsciously tapping into something we're all searching for: a place for possibility. Threads feels like the first day back to school; all your friends are already there, and it’s exciting to be together again.

The Ties that (un)Bind Us

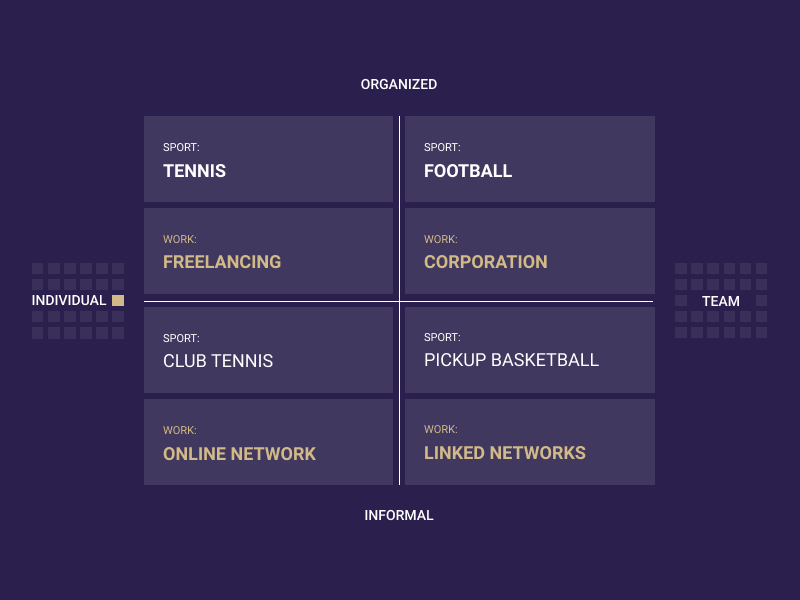

The rise of remote work has morphed the way that online interactions shape our work, our lives, and our minds. Since social networks have become a place for personal and professional connections, our online presence—and our point of connection—is more important than ever.

Sociologist Mark Granovetter studied how functioning societies are underpinned by what he called "strong" and "weak" ties. Strong ties refer to our close relationships with friends, family, and even colleagues. As you might expect, weak ties refer to the more casual ties that form within our network.

A recent study found that email data among MIT's faculty showed a 38% decrease in weak ties during the pandemic, which resulted in 5100 net-new weak ties lost within 18 months. This indicates that, while social media has brought us more online, it has a larger impact on our overall social connection. We’re more online, but less connected.

The future of work will be distributed across these online networks, and so these connections play an increasingly important role in our personal and professional lives.

I can’t pretend to offer advice on how to use social media. I ghosted all social media for the better part of the pandemic, which was fantastic. I'm back now, but not everywhere, and not all at once.

But we need networks built for actual connection, not just another clone of the online networks built a decade ago.

We The People…Matter

For me and many, Twitter started as a place to meet great people, share things with people you know, and keep up with news and current trends. But those days are long gone, and here we are, fighting to stay alive as we navigate each new tool and platform that comes our way. That's just the reality of social platforms; they start out pure, and slowly erode into divisive, corrosive, punitive discussions among strangers.

“We shape our tools and thereafter our tools shape us”

Like everything, software products and platforms can be corrupted. New products rarely change old behaviors. If I were a betting man, I'd bet that Threads would fall into the same traps that Twitter fell into.

Since Elon Musk took over Twitter, I've read countless tweets about people leaving Twitter for Bluesky and Mastadon, all in protest of Musk. (Don't get me started on the irony of using the platform you're leaving to announce your righteous departure to the latest and greatest.) And the same pattern is repeating itself with Threads.

The factions that arose during the transition seemed eager, enthusiastic, but potentially senseless. While many users did leave, others doubled down on the platform.

Those who did leave likely ported their Twitter behaviors to their new platform. And who's to say we will see a different pattern with those switching to Threads. If the behaviors are the same across platforms, at the end of the day, is there any meaningful difference between these networks? Further, what would it take to drive meaningful change?

The only way to change: if people change.

What is created on these platforms is determined not only by the UI and features, but also by the people. We, as users, have an opportunity to reshape what we want from our online social connections. The longing for something new is less about the disdain for figureheads like Elon Musk, and more about the appetite for personal social networks. Networks that mimic our real-life interactions without the posturing and cringe discourse found on Twitter and LinkedIn.

The Path to Rebuilding Personal Networks

So, is Threads the future? I have no idea. And honestly, it's not what I care about. I care about how we work and live in a world where online social networks are a core part of our existence. I care about keeping our minds sharp, building stronger relationships, and finding ways to lift each other up.

Reflecting on the social networks I've used and my experience with each, I realize they all follow a similar path: honest communication > genuine interactions > professional posturing > branding, building, and selling > trolling. That is, except for one of the OG networks: Path.

If you're not familiar with Path, let me explain.

Path was a mobile app launched in 2010 and allowed users to share personal updates with a maximum of 50 contacts. Though it eventually shut down, the ideas it embodied were way ahead of their time. Instead of asking users to follow everyone and be "friends" with thousands of people, it used constraints to its advantage, allowing users a max of 50 connections and a host of features that shared content out to other platforms, keeping you from the dreaded doom-scrolling that plagues all modern social networks.

This quote from Dave Morin says a lot about the philosophy behind Path:

“What would you expect in your home? What would you expect in your personal life? A lot of the types of content we allow people to share has direct impact on people’s personal lives.”

Path was really more about ego networks than social networks. If you're unfamiliar with ego networks, they're a type of network that specifically maps the connections of and from a single person's perspective.

We don't often think about it, but we each have a mini-universe. We have friends and family that connect to and through us. We know the level of connection we have with each of them. We have a mental model of how we're linked and the strong or weak ties, frequent and infrequent contact.

This is what Path understood. And this is what we need from our online networks.

So how might we rebuild personal networks with the goals of having a direct impact on people's personal lives?

I'm not going to claim to know the answer to our social media puzzle, but it's in our best interests to rethink the ways we interact with each other online.

Here are the principles I'm going to follow:

Build relationships, not followings. Our goal is to be social, which implies we should build relationships. Followings are great, but they can be shallow and fickle. Relationships grow, change, and evolve. Instead of authenticity, followings encourage the personification of personalities.

Connect, don't capture. Social media has conditioned us to focus on capturing our audience and sharing content that builds a brand. Instead, if we aim to exist and develop genuine connections through authentic content, we may find that the actual connection doesn't require such posturing.

Live, don't lie. Our ability to build relations and connections hinges on being ourselves. Too many social platforms encourage maintaining a persona or brand. It's time to ditch the lies of the persona and embrace honesty in our personal and professional communication.

If you agree, feel free to steal these. If not, drop me a comment with suggestions.

If you're enjoying Threads—and I hope you are—then keep at it. If, like me, you feel uncomfortable looking in the funhouse mirror that Meta created, I hope you feel encouraged to step away from the pressure to join yet another network. Until I feel more confident that Threads will improve the current social media traps, I plan to remain a Threads lurker.

Regardless of your feelings on the leaders, features, and culture of these products, if you're going to use them, I have one recommendation: use them to build an authentic personal network, not a social network.

It’s time our tools help us develop places for possibility, not just profit.

Paths to Prosperity

MVF as a Tool to Achieving Financial Freedom

Recently, a friend of mine quit her job. She left with:

No backup plan.

No safety net.

No plan to return.

No, this wasn't some impulsive reaction to a subpar meeting with a manager or something mundane. The roots of the quitting had been building for years. Her fast-paced startup employer pushed her in every way possible — working insane hours, decreasing headcount, and promising titles and promotions that never came. The list of bad experiences was long. All this left her burnt out, overworked, under-appreciated, and underpaid, and I can fully relate.

However, these instances of burnout and disillusionment are not isolated incidents. According to a recent report by Deloitte, 60% of employees are thinking about leaving their job for one that better supports their mental well-being. A recent LinkedIn study found that almost 70% of Gen Z and millennial Americans plan to leave their jobs in 2023. If it's not clear, workers are not having it.

The Dependent vs Independent Mindset

When I first left my salaried position in 2015, I thought I knew what I was doing. Once the money started coming in, I thought everything would be simple.

I had a salaried mindset, and a dependent mindset.

Meaning: I was looking at my potential earnings and comparing them to my compensation as a salaried employee because that's all I understood then. I figured, okay, if I made $X/year as an employee, I need to get my business(es) to make that much, and it will work. Forget taxes, business expenses, etc. — that was all I needed.

Surprisingly, as most entrepreneurs find out, I realized that I needed both more and less than I thought; because money is different for entrepreneurs. You need more, because the government wants a lot more of it. You need less, because your life changes. Your needs change. Your wants change. Your drive changes.

A salary is a tradeoff for part of your soul. It's not just money, it's potential. Your potential to find joy, value, and a satisfaction on your own path. Potential is hard to quantify, but it's safe to assume it's worth much more than your salary.

For years, I had the wrong mindset. I associated money with success, and therefore I always wanted more. To this day, I still struggle with it.

What changed?

I changed my definition of enough by defining my MVF.

What is MVF?

After realizing that just replacing my salary was not a reasonable calculation for my work or the goals that represented a life well-lived, I decided to make a new calculation. A calculation that would capture the financial thresholds that I wanted to reach, keeping me from the hedonic pursuit of 'more.'